how we pay for software

Quality software costs money to make.

The tech industry has backed itself into a corner in the last couple decades by implying to users that software doesn’t cost much. Google led the charge here, by providing a series of useful and well-made applications like Gmail, Google Maps, and its core search product for free. They aren’t free, of course: users ”pay“ with their attention and personal data for advertisements.

Paying with attention and personal data is probably a good trade for search and maps, maybe less so for email. But it’s not a model that fits professional and creative tools.

Here are three proven models for paying for software:

Ad-supported software. Only really appropriate for pure-consumer products that are attention-oriented to begin with (e.g. social media). Requires huge scale since each user is only worth a few bucks. Because the user is the product rather than the customer, the user’s needs are not the priority of the business.

Software bundled with hardware or content. End users seem to be fine with paying directly for hardware (smartphone, laptop) or content (Netflix, Spotify). In these examples the software is a huge part of what you’re paying for—a Mac without macOS is just an overpriced PC, and Netflix without its excellent browsing and playback software is just cloud storage media stocked with MP4 files. Yet few people think of themselves as paying for macOS or Netflix’s app.

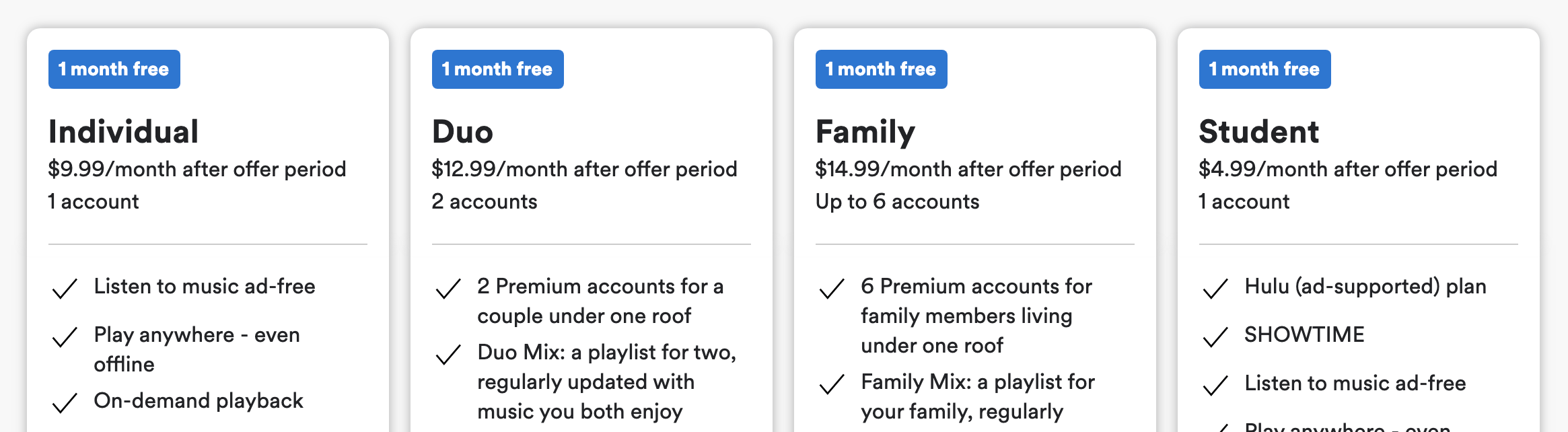

Spotify’s pricing demonstrates the common price range for individually-purchased subscriptions: $5/month on the low end, $15/month on the high end.

B2B SaaS. ”Business-to-business software-as-a-service“ is a mouthful, but represents a a beautiful, pure, and simple payment model for software. A business has a problem; a software creator offers a web-based product that solves the problem; the business purchases directly from the creator, and continues to pay as long as they have the problem and the product is good. Interests are aligned, and the no-middleman nature of the web means software creators have a direct relationship with their customers. Everybody wins. That’s why there’s so many success stories here: Slack, GitHub, Mailchimp, Atlassian, Zoom, Notion, and Carta just to name a few.

I seek a world with a great diversity of lovingly-crafted software for niche audiences. But niche is not possible with ad-supported which requires huge scale to work, and hardware and content licensing have massive up-front capital costs that imply financing models not compatible with small-scale.

Happily, B2B SaaS is having its revolution for small independents right now. So what’s the equivalent of that for pro creator tools like video editing or writing or knowledge management? Can we have something as beautiful and pure as B2B SaaS but for individuals as well as businesses, and for desktop, mobile, and other native apps?

And indeed there does seem to be movement toward subscription-priced prosumer products in the $5 – $15/month range. See established players like Dropbox, Evernote, Ulysses and OmniFocus; plus up-and-comers like HEY, Roam, Descript, and my own venture Muse.

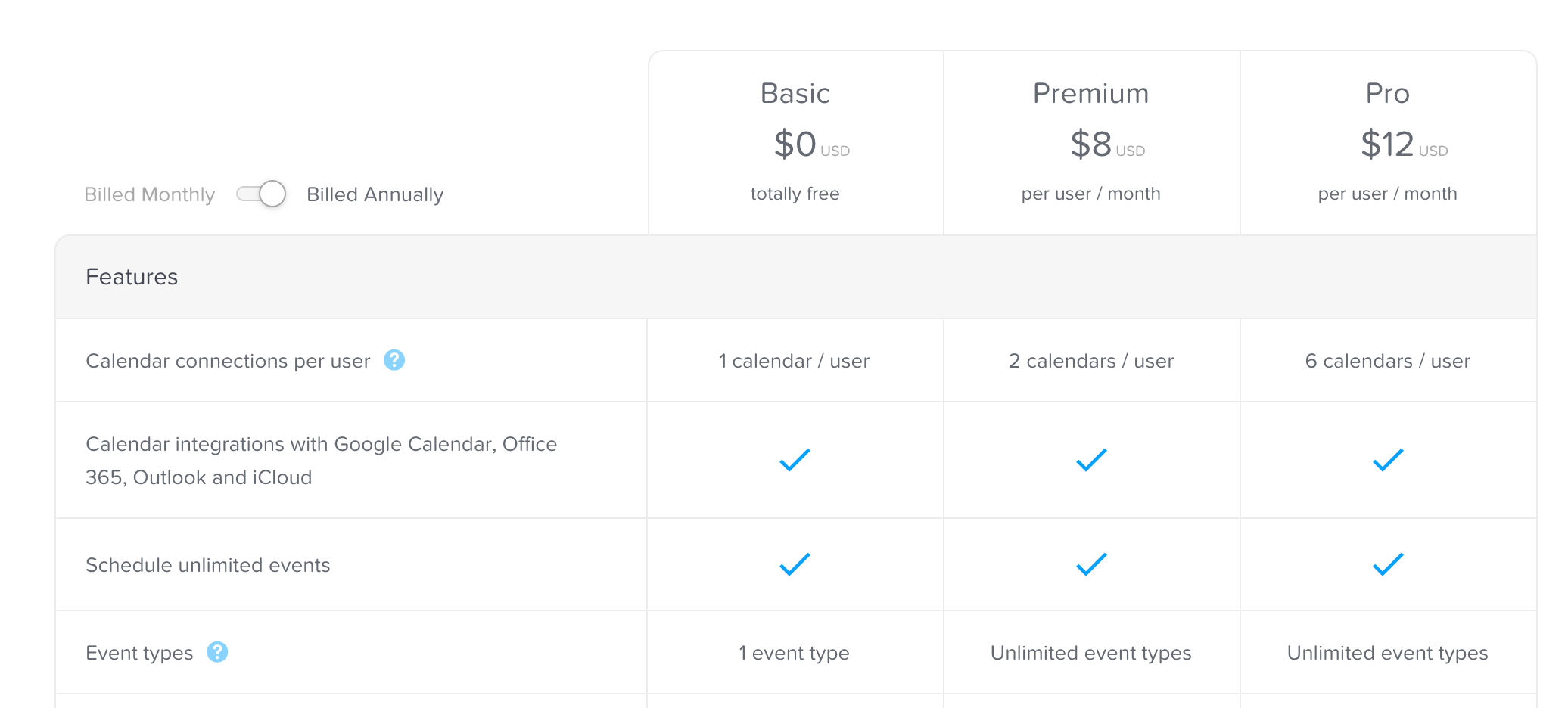

Calendly’s pricing is similar to other prosumer products.

As a user customer, I like the idea of finding a few great tools that empower my work and paying for them directly. That gives me confidence the product will serve my needs long-term, because I’m the customer.

And this doesn’t mean a bigger budget for my tech product purchases overall: I can subtract these subscriptions from the money I previously spent on a new phone and laptop every two years, then buy new hardware a little less often. Right now I think great software is more important than hardware advances, much as I love shiny new devices.

As a software creator, I love the idea of serving a niche of customers who are deeply connected with the product I’m making and get lots of value from it. It has that pure, direct, and personal relationship we see in B2B SaaS, but maybe even more initimate because these are personal tools.

Ok sounds good—but now the next problem with a direct-payment model. If we’re going to make software subscriptions work, we as creators have to address the sharp edges and subscription fatigue people may experience maintaining a stack of software subscriptions.

Individuals are cautious about recurring billing due to poorly-designed—even borderline scammy—subscription buying, renewal, and canceling experiences. The reference worst-case scenario are gym memberships or mobile phone contracts: being trapped in a recurring payment that no longer fits your needs, and being forced to navigate a customer service maze to try to downgrade or cancel.

So how can we give customers a great experience with subscriptions? A few proposals:

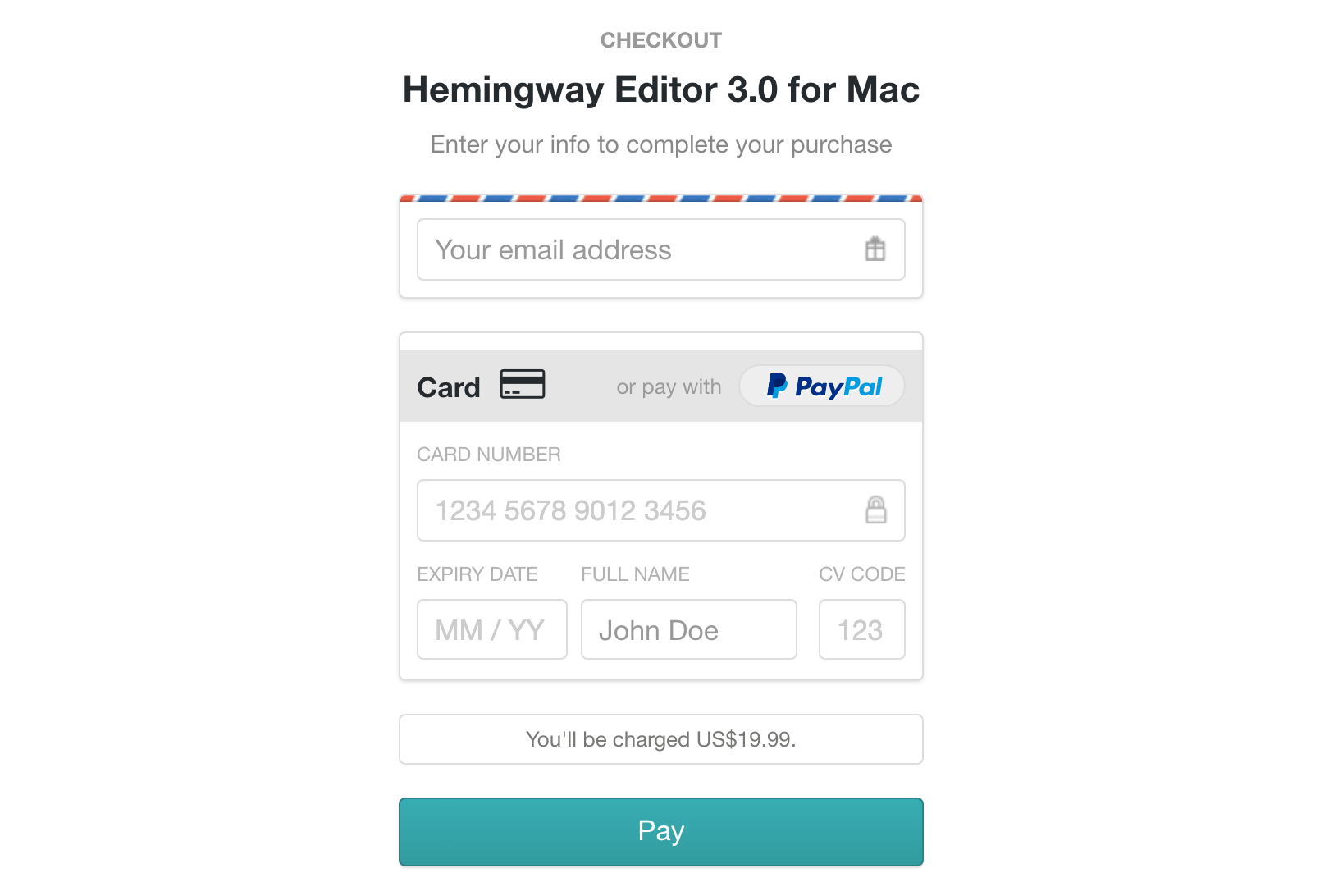

Treat the buying experience as part of your product. Make it easy for prospective customers to see what they will get; making buying easy and fun; show them love afterward, not just a ”you’re all set“ dialog and nothing else.

Gumroad offers a great buying experience with a minimum of fuss.

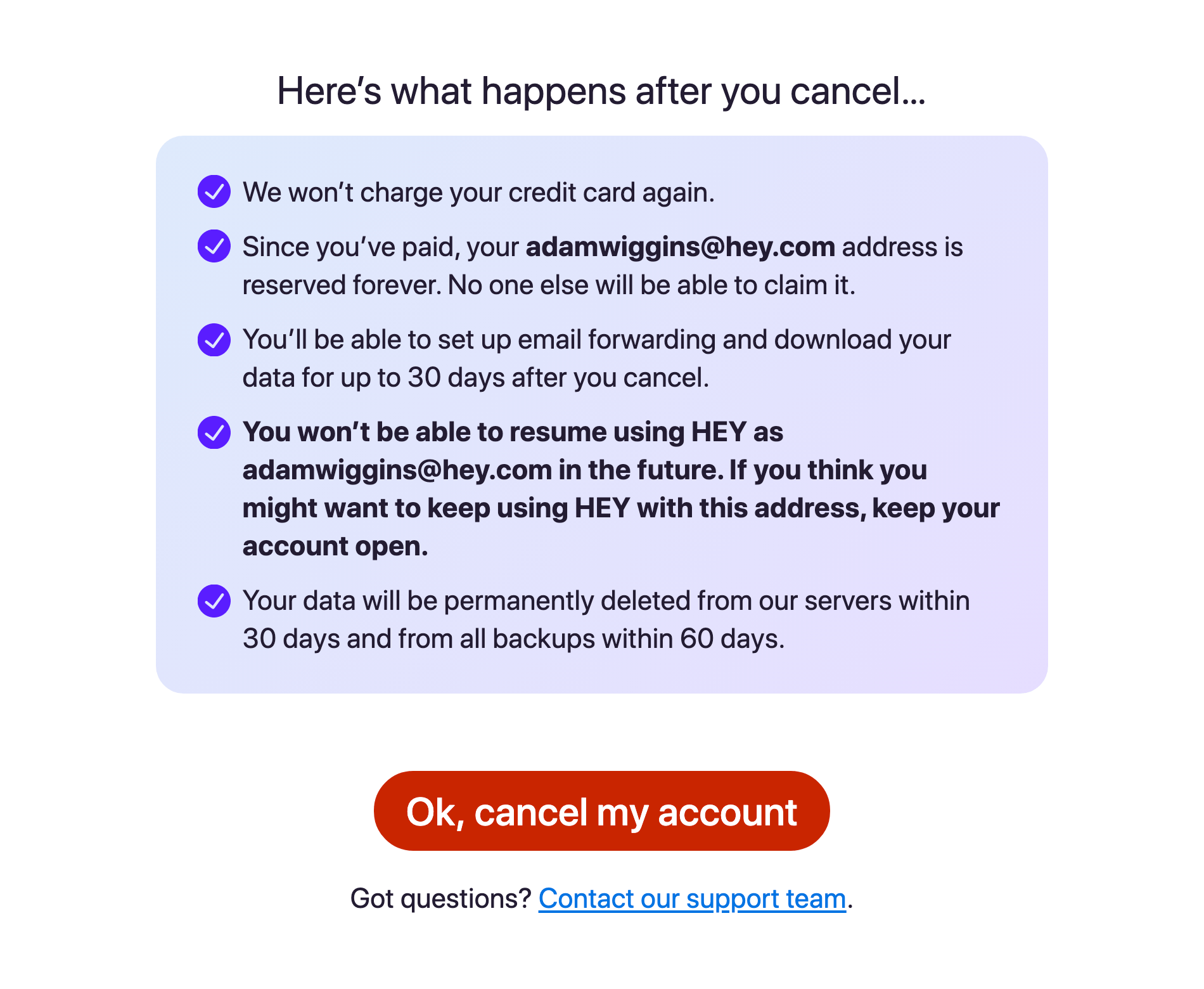

Make it easy to cancel at any moment. Canceling should be as smooth as purchasing initially. For bonus points, give a refund for any unused portion of purchased time.

For longer-cycle payments (e.g. annual), give heads-up notifications before payment so that users are not surprised. Direct them on how they can cancel with just a couple of clicks. You shouldn’t want any money from someone who is no longer getting value from your product.

HEY makes canceling easy: just two clicks. The confirmation dialog is clear on exactly what happens next.

Don’t lock users out of their data, even if their trial runs out or their subscription ends. Make it easy to get at their data and export for use in other places.

Don’t treat lapsed or canceled subscriptions as strangers or defectors. Instead, consider them alumni and offer them your respect and maybe even some extra perks. They’ve been customers in the past, so be thankful for that. Remember they might return as a customer in the future or refer other potential customers.

Slack delights and surprises with their fair billing policy.

Beyond prosumer subscriptions, I’m happy to see products experimenting with models appropriate to their domain, like the ski app Slopes offering packs of day passes; time-based notes app Agenda with feature unlock based on subscription time windows; and Komoot with hiking region bundles for sale.

One last one I find especially promising is the half-crowdfunding, half-early-purchase model that’s seen success with video games, films, and typefaces. This blurs the distinctions between customer, investor, and donor. When you buy a Steam Early Access game you’re saying not just ”I want to purchase this product“ but also ”I believe in this product and the team behind it; I want it to exist; and I’m willing to risk a bit of my money to make that happen.“ And maybe: ”I like getting to give early feedback and influence the outcome of the finished product.“ Wikipedia with its pure patronage model and Are.na with its earnings transparency are variations on this theme.

The world we have: Almost all software is paid for by (1) ads and selling personal data (2) bundling software with hardware or content or (3) business-purchased subscriptions. As a result, the type of software we have is limited to what will fit in those boxes.

The world I want: A wide diversity of funding and payment models for pure software products. Prosumer subscriptions are commonplace; users feel great about buying tools that matter to them; and they get a great experience when buying and canceling. Crowdfunding, patronage, and many other models flourish and individual products can choose the model that best fits them and their customers.